I have a view of morality which differs quite a bit from what most people probably understand morality to entail. I’ve wanted to consolidate my thoughts on it for some time. In short, my view is that we have an innate moral capacity, which we develop through socialization throughout our lives, and which primarily operates without conscious effort or thought. The way our capacity for moral judgments actually operates is separate from the way we justify our moral judgments, which can make our debates about morality… let’s say, a bit difficult.

I’ll start with a very brief account of the primary traditional views of morality.

The Traditional Views

It’s an election year in the United States and it looks like people will have to choose between Biden and Trump. Many progressives are debating whether to vote for Biden. Some people say “no matter how bad Biden is, Trump would be worse, and you should vote for the lesser of two evils.” Others say “no matter how bad Trump is, I can’t bring myself to vote for someone who has armed Israel with weapons to use against Palestinian children.”

Of course there are other positions - centrists, conservatives, etc. - but I’m highlighting the two progressive camps to illustrate a specific moral question. And it is a question, even though people on both sides seem to believe they have the answer and the other side is stupid, evil, or both.

The question is, when you evaluate the morality of an action, do you look at the action itself, in isolation, to see if it follows your moral rules? Or do you look at the action in context and decide whether it makes the world better or worse than an alternative action? The first point of view is what moral philosophers call “deontology”, and the second is “consequentialism”. The most prominent version of consequentialism is called “utilitarianism”.

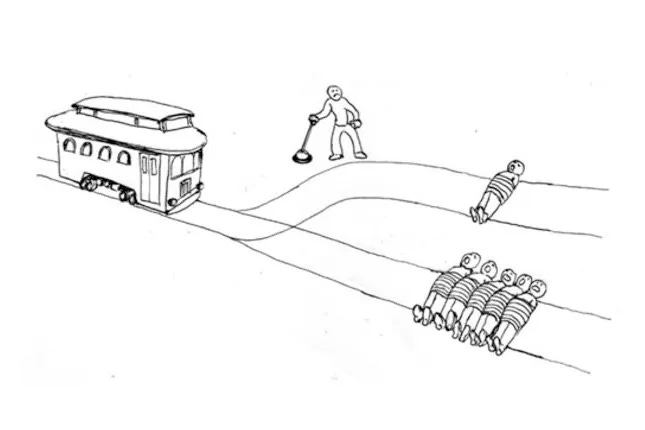

It turns out it’s not really possible to decide which of these ethical systems is “correct” - people typically have moral intuitions which accord with one or the other based on the specifics of the situation and often in ways which are not clearly understood. The most classic illustration of this starts with the “trolley problem.”

You’ve probably heard of this, and seen the meme of it by now. There is a train speeding down a track towards five people, who will all die if you do nothing. If you pull the switch it will move to an alternate track and only kill one person. What should you do?

Most people have the utilitarian intuition here - they say you should sacrifice one person to save five.

But if you change the form of the problem, this intuition goes away. For example, suppose there are five patients each in need of an organ transplant - one needs a heart, one a lung, one a kidney, etc. - and there is a doctor who can save each of these patients by killing one healthy patient and redistributing their organs. Under these circumstances, it no longer seems morally permissible (again, to most people) to save five people by killing one.

Questions of morality are not reducible to simple questions of quantity, and instead are linked to concepts such as agency, responsibility, urgency, directness, attenuation, salience, certainty, and perhaps other unconscious factors that no one has yet identified! Personally I find it thrilling that nobody really knows how to predict how we might decide moral questions in any given situation.

It does seem though that in the particular issue of voting this question is particularly divisive, probably because a lot of the concepts I mentioned above are involved. How much responsibility do I bear for the actions of someone I vote for? If I vote for person A and person A enacts policy B which enables person C to kill person D, am I sufficiently far away from person D on the chain of causality to avoid moral responsibility? If voting for A might or might not result in person D’s death, how does that impact my responsibility? Am I morally responsible for everyone, or only people in my own country? In my own city? In my own family?

I don’t think the moral question even has an answer. However, in practice, most people will, in fact, answer the question. How do they do this?

Moral Judgments and Intuitions

I believe that in most situations which call for a moral judgment, we first unconsciously render that judgment based on intuition. In other words, the answer just sort of materializes in our minds, manifesting as a sort of feeling or sense of either rightness or wrongness. Later on, we might rationalize this judgment by making reference to whatever moral framework happens to support it.

If we can think of an obvious moral rule, like “murder is wrong”, we might behave like deontologists, and cite the moral rule. If our judgment happens to line up with the greater good, we might behave like utilitarians, and explain how our judgment produces the best outcome.

Note that we usually don’t do this, at all. When we see something we think is bad, our response is “that’s bad” - not “that’s bad because murder is wrong” or “that’s bad because it hurts a lot of people”. We typically only make reference to a moral principle if we’re challenged to come up with a defense or explanation for our initial judgment. This follows my belief that in general we make most decisions unconsciously, and only exceptionally difficult decisions are made with the assistance of the conscious mind.

For example, when you read earlier about the question of whether a doctor should kill a healthy patient to provide life-saving organs to five other people, you probably didn’t think “okay, well first let me decide whether I want to apply a deontological or utilitarian moral framework to this question”. Instead, you probably thought “hell no, that’s horrifying”. That part is your moral judgment. Everything that came after is just a rationalization for it.

Where does our moral intuition come from? To an extent, it’s innate. There is a strong body of evidence on infant morality (there’s a review here with no paywall) which suggests that infants innately possess a preference for helping others as well as a preference for people or characters who help others. Humans are naturally a social and cooperative species so it makes sense that the necessary behaviors of cooperation and mutual aid would have some cognitive component. In other words we often find things necessary for our survival and reproduction to be “good” or pleasurable - like eating food, say - so in the same way that we might experience food as having a good flavor, or sex as having a good physical sensation, we experience pro-social, cooperative behaviors as having a good moral character. In this sense, our “sense” of morality is similar to our “sense” of taste and our other physical senses.

However, morality is not as simple as an aesthetic preference for good behaviors. Our experience of morality can be influenced by context and shaped by experience, including our experience of our culture and society - the same way our tastes can develop and be refined over time. We may come to associate morality with our identity and seek to attune our sense of morality with other members of our group. We might try to train our moral intuition in order to better fit in to our society or our chosen faction therein.

Furthermore, the organization of our society may shape our morality. If our moral judgments tend to favor helpful and pro-social behaviors, then societies in which different sorts of behaviors are helpful may end up producing different moral intuitions. As technology expands our ability to communicate globally, our pro-social instincts may come to encompass people in faraway places. As science expands our ability to predict the consequences of our actions, our instincts may extend to helping future generations of people. If morality is fundamentally about helping people, then we need to decide exactly who we are morally obliged to help. Some of us may count animals as “people” and may consider it immoral to harm them, even to the extent of becoming vegetarian or vegan.

Conversely, we may find ways to exclude others from our moral intuitions. Moral atrocities are often preceded or accompanied by a process of dehumanizing the victims so that helping them is no longer a moral imperative and harming them becomes morally permissible.

Grassroots Morality

This account of morality differs quite starkly from traditional understandings of moraltiy which may describe morality as some kind of natural phenomenon, which might be either located in nature, discovered through introspection, or revealed by a divine force. You will often hear religious people claim that atheists cannot have morality, because morality comes from God. Yet the evidence suggests otherwise: we begin making moral judgments long before we can be taught religion, which is why certain fundamental moral principles are consistent across religions and even between theists and atheists. Meanwhile, we don’t actually follow all of the ethical rules in our religious texts, but rather pick and choose the ones we feel are relevant to our particular societies and circumstances, discarding the others. If morality comes from the Bible, then on what basis do we decide that the Bible was right about murder being wrong, but wrong about slavery being right? Clearly, in practice, we apply the same moral judgment to our religions as we do to everything else we experience, which implies that our moral judgment is something which develops at least somewhat independently of our religious beliefs.

And yet, many people still talk about morality as if it is simple, absolute, and crystal clear at all times. I think there are pragmatic reasons why we might want to make moral assertions with certainty, but I think it is also important to be able to step back from them and understand the reasons why people may have differing moral intuitions, especially on questions as complicated as whether you should support a morally problematic political candidate.

Morality is difficult precisely because it doesn’t come from any authoritative source. It comes from people. It comes from within us, and it arises from our need to cooperate with each other. Our fundamental moral intuitions may be innate, but we hone and calibrate them in concert with others. When we are in accord with the morality of our social group, we experience harmony, and when our moral intuitions contradict those of our social group, we experience dissonance. Morality doesn’t come from above.

Morality is grassroots.

Good read, thanks for posting. Philosophers from Hegel to Kiergegard to Nietzsche have considered this question for a long time.